Compiled by Peter Schipper

THE BIRTH OF JESUS

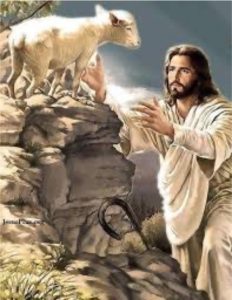

This is how the birth of Jesus Christ came about: In the sixth month, God sent the angel Gabriel to Nazareth, a town in Galilee, to a virgin pledged to be married to a man named Joseph, a descendent of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. The angel went to her and said, “Greetings, you who are highly favored! The Lord is with you.”

Mary, greatly troubled at his words, wondered what kind of greeting this might be. But the angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary, you have found favor with God. You will be with child and give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father, David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever. His kingdom will never end.”

“How will this be,” Mary asked the angel, “since I am a virgin?”

The angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you, so the holy one to be born will be called the Son of God. Even your relative, Elizabeth, who was said to be barren, is going to have a child in her old age and is in her sixth month, for nothing is impossible with God.”

“I am the Lord’s servant,” Mary answered. “May it be to me as you have said.” Then the angel left her.

Mary was pledged to be married to Joseph, but before they came together, she was found to be with child through the Holy Spirit. Because Joseph her husband was a righteous man and did not want to expose her to public disgrace, he had in mind to divorce her quietly. But after he had considered this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary home as your wife because what is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will deliver his people from their sins.”

When Joseph woke up, he did what the angel of the Lord had commanded him and took Mary home as his wife. He had no union with her until she gave birth to a son.

All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet Isaiah: “The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and they will call him “Immanuel,” which means, “God with us.”

In those days Caesar Augustus issued a decree that a census should be taken of the entire Roman world. This was the first census that took place while Quirinius was governor of Syria. And everyone went to his own town to register.

So Joseph also went up from the town of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to Bethlehem the town of David, because he belonged to the house and line of David. He went there to register with Mary, who was pledged to be married to him and was expecting a child. While they were there, the time came for the baby to be born, and she gave birth to her firstborn, a son. She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn. And they gave him the name Jesus.

And there were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over the flocks at night. An angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all the people. Today in the town of David, a Savior has been born to you; he is Christ the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

Suddenly a great company of the heavenly host appeared with the angel, praising God and saying,

“Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace to men

on whom his favor rests.

When the angels had left them and gone to heaven, the shepherds said to one another, “Let us go to Bethlehem and see this thing that has happened, which the Lord has told us about.”

So they hurried off and found Mary and Joseph and the Baby, who was lying in the manger. When they had seen him, they spread the word concerning what had been told them about this child, and all who heard it were amazed at what the shepherds said to them. But Mary treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart. The shepherds returned to their fields, glorifying and praising God for all the things they had heard and seen, which were just as they had been told.

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi from the east came to Jerusalem and asked, “Where is the one who has been born King of the Jews? We saw his star in the east and have come to worship him.“

When King Herod heard this he was disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him. When he had called together all the people’s chief priests and teachers of the law, he asked them where the Christ was to be born.

“In Bethlehem in Judea,” they replied, “for this is what the prophet Micah has written:

‘But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah,

are by no means least among the rulers of Judah;

for out of you will come a ruler who will be the

shepherd of my people Israel.’“

Then Herod called the Magi secretly and found out from them the exact time the star had appeared. He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and make a careful search for the child. As soon as you find him, report to me, so that I too may go and worship him.”

After they had heard the king, they went on their way, and the star they had seen in the east went ahead of them until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshipped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold and frankincense and of myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their country by another route.Matthew 2:1-12; Luke 1:26-38; 2:1-20.

OUR CHRISTMAS TRADITIONS

The Date of Christmas. It is highly unlikely that Jesus was born on December 25, for the nights in Israel between December and February are exceptionally cold. Jesus himself alluded to this in Matthew 24:20 and Mark 13:18, referring to the signs at the end of the age: “Pray that your flight will not take place in winter … ”

The Date of Christmas. It is highly unlikely that Jesus was born on December 25, for the nights in Israel between December and February are exceptionally cold. Jesus himself alluded to this in Matthew 24:20 and Mark 13:18, referring to the signs at the end of the age: “Pray that your flight will not take place in winter … ”

In the 13th century, the rabbi and philosopher Maimonides commented on the weather and the tending of stock around Jerusalem: “These cattle lie in the pastures, which are in the villages, all the days of the cold and heat, and do not go into the cities until the rains descend.” In Israel, the first rains usually fall in the Hebrew month of Marchesvan, which covers the latter part of October and the beginning of November. This being the case, it is likely that the cattle mentioned in the birth accounts in Matthew and Luke were in the fields prior to the winter months, making it probable that Jesus’ birth occurred either in the fall or perhaps the spring.

Further, the harsh winter weather in Israel would not have permitted the travel necessary for the people to go to their various towns of origin for the Roman taxation. The order for taxation would likely have been given during a time when the roads were clear and weather conducive to travel.

Some recent scholarship places the actual birth of Jesus somewhere between 5 and 8 AD, in conjunction with the death of Herod the Great. This date also correlates with the convergence of Saturn, Jupiter and Mars, which many believe to have been the star followed by the Magi.

The December 25 date was arrived at through a process of syncretized tradition. At the close of the second century AD, Clement of Alexandria, writing in his book, Stramata, mentions that many of the early churchmen believed the dates of Christ’s birth and baptism to have been the same. Augustine, in his fifth century work de Trinitate, remarks on the prevailing tradition in the Western church, “For he is believed to have been conceived on the 25th of March (9 months before December 25), upon which day he also suffered … but He was born according to tradition upon December the 25th.” Even now, some twenty centuries later, the Roman Catholic church recognizes and celebrates the Annunciation and the Immaculate Conception on March 25, which is also the date of the ancient Roman celebration of Matronalia, or Lady Day.

In the fourth century, the Emperor Constantine, on becoming a Christian, made no exclusion between his new faith in Christ and his old faith in the Roman sun-god Mithras. The Roman transition from their popular form of pagan solar monotheism to a Christian monotheism with solar inferences was not difficult, the syncretism being facilitated through the prophet Malachi’s type of Christ, “But for you who revere my name, the sun of righteousness will rise with healing in its wings”(4:2). Clement of Alexandria, around 200 AD, had referred to “Christ [as] driving his chariot across the sky like a sun-god mounting the heavens in his chariot,” and Tertullian, another early church father, wrote that many pagans imagined that Christians worshipped the sun because they met on Sundays and prayed toward the East.

Historically, the Romans enjoyed a succession of winter solstice celebrations between December 17 and 25. Saturnalia, the celebration of the Roman festival of Saturn, was a time of remembrance of the golden days of the empire and was celebrated on December 17-18-19. During this time, all schools and public businesses were closed and no legal proceedings could be transacted. Saturnalia was quickly blended with Sigillaria, the Festival of Images, probably held on December 21 or 22, and was a time of exuberant public festivities, complete with parades and the wearing of masks.

Brumalia, the celebration of the shortest day of the year, followed, marking the winter solstice when the sun is at the northernmost point of its ellipse, which occurs on December 22. It was at this time the Romans revered the overcoming of darkness by light, of evil by good, and the passage of winter into spring.

Juvenalia, the Celebration of the Children, occurred on December 24, and was marked by gift-giving and tree decoration. This holiday appears to have been syncretized by the Romans out of both the Chaldean Eol (Yule?) day and the Arab celebration of the birthday of their moon god, Meni, both on December 24; the birthday of Mithra, the Persian god of light, was December 25.

It was around the year 325 AD when these winter solstice days of celebration of December 17 through 25 were syncretized by the official Roman Christian church to represent the birth of Christ, or Christes Maesse, Christ Mass. The first recorded date of the celebration of Christmas was mentioned by Bishop Liberius of Rome around 360 AD, when he referred to December 25 as the Lord’s birthday. By 380, Christians in Syrian Antioch are documented as celebrating Christmas, and by 430, Christmas is recorded as being celebrated in Alexandria in Africa.

By 590, December 25th had become a tradition and Pope Gregory implemented the Advent Calendar to signify a time of solemn prayer in preparation for the remembrance of the coming of Christ. Advent and Christmas were immediately followed by Epiphany as a recognition of Christ’s manifestation to the Magi and the gentile world.

The Manger and the Inn. The Greek word for manger, phaten, (Luke 2:7, 12. 16) refers to a relatively large box or rack containing hay for feeding cattle. This word occurs only in Luke. Phaten may also designate a stall in which animals are fed, a part of a barn, or a customary enclosure place where animals are fed.

The Manger and the Inn. The Greek word for manger, phaten, (Luke 2:7, 12. 16) refers to a relatively large box or rack containing hay for feeding cattle. This word occurs only in Luke. Phaten may also designate a stall in which animals are fed, a part of a barn, or a customary enclosure place where animals are fed.

The inn, also known as a caravansary, was usually built with thick outer walls and secure gates for protection from bandits and marauders and provided three classes of accommodations. The upper level was comprised of separate rooms for wealthier travelers, usually the merchants in charge of the caravans. Along the periphery of that same structure would be a continuous terrace for the less wealthy; here, they could create some sense of privacy by hanging up blankets or robes. The poor could usually find some space for a bedroll on the ground level, among the camels and donkeys. On the night Joseph and Mary arrived, it is likely that all of the better accommodations were taken, and that accommodations on the ground-level would have been unsuitable for a woman to give birth. The early church believed the manger to have been a cave, which finds substantiation in archaeological discoveries of a large number of mangers hewn out of native limestone caves.

The Star of Bethlehem. The nature of the star which guided the Magi to the Christ child is unspecified. It may have been a manifestation of the shekinah glory (Exodus 16:10; 25:22), a comet (Halley’s comet was visible in 12 B.C.), or the appearance of a special constellation, just for that time. Some scholars propose the star was the convergence of Saturn, Mars and Jupiter, which has been calculated to have actually occurred in 7 BC and recurred again in 6 BC. Others posit that is was the triple conjunction of Regulus (the king star), Jupiter (the king planet, also referred to as sedeq, meaning ‘Messiah’) and Venus (symbolic of love and fertility) that occurred in June of 2 B.C. and would have appeared as a bright beacon of light. As the Magi approached the house in Bethlehem, such a ‘star’ would have been low enough in the sky to appear to touch the roof of the house they sought.

The Star of Bethlehem. The nature of the star which guided the Magi to the Christ child is unspecified. It may have been a manifestation of the shekinah glory (Exodus 16:10; 25:22), a comet (Halley’s comet was visible in 12 B.C.), or the appearance of a special constellation, just for that time. Some scholars propose the star was the convergence of Saturn, Mars and Jupiter, which has been calculated to have actually occurred in 7 BC and recurred again in 6 BC. Others posit that is was the triple conjunction of Regulus (the king star), Jupiter (the king planet, also referred to as sedeq, meaning ‘Messiah’) and Venus (symbolic of love and fertility) that occurred in June of 2 B.C. and would have appeared as a bright beacon of light. As the Magi approached the house in Bethlehem, such a ‘star’ would have been low enough in the sky to appear to touch the roof of the house they sought.

The Witnesses to Jesus’ Birth. Present at the birth of Jesus were Mary and Joseph, and later a few shepherds who came from the fields to visit the Christ child, in response to the annunciation by the angels. It is likely that the infant Jesus, upon his birth, would have been rubbed with salt to prevent infection, and then rubbed with olive oil and perhaps even with powdered myrtle leaves before being wrapped in swaddling, strips of soft linen. Scripture does not indicate that angels, cattle, or the Magi were present at the manger.

The Witnesses to Jesus’ Birth. Present at the birth of Jesus were Mary and Joseph, and later a few shepherds who came from the fields to visit the Christ child, in response to the annunciation by the angels. It is likely that the infant Jesus, upon his birth, would have been rubbed with salt to prevent infection, and then rubbed with olive oil and perhaps even with powdered myrtle leaves before being wrapped in swaddling, strips of soft linen. Scripture does not indicate that angels, cattle, or the Magi were present at the manger.

The Magi. The term magi comes from the Greek magoi, meaning ‘magician.’ The third century historian Herodotus identifies them as priests from the ‘nation of the Medes’ (Persia, or present-day Iraq), and it is likely they were astrologers rather than kings. Armenian tradition identifies the magi as Balthasar of Arabia, Melchior of Persia, and Gaspar of India.

The Magi. The term magi comes from the Greek magoi, meaning ‘magician.’ The third century historian Herodotus identifies them as priests from the ‘nation of the Medes’ (Persia, or present-day Iraq), and it is likely they were astrologers rather than kings. Armenian tradition identifies the magi as Balthasar of Arabia, Melchior of Persia, and Gaspar of India.

The Magi were not present at Jesus’ birth, but came approximately a month or so later, visiting the baby Jesus after Joseph and Mary had moved into a house (Matthew 2:11). The number of the Magi is not specified, and according to whatever tradition is most familiar, their number can range anywhere from three to four to twelve to forty. It is often assumed there were three Magi because three gifts were given.

The Gifts of the Magi. The word ‘frankincense’ comes from the Old French franc encens, or ‘pure incense.’ This is a fragrant balsamic resin coming from the Terebinth tree, native to Southern Arabia and India, and was used ceremonially by the Hebrews. Myrrh is the dried resin of the low-growing, thorny Cistus tree, or Rock Rose, also native to Southern Arabia and Ethiopia, and, at one time, to Palestine. This was used as a perfume base and is one ingredient of the anointing oil prescribed in Exodus 30:23. It was highly valued as a cosmetic, a deodorant, and a medicine. The Egyptians used both frankincense and myrrh in embalming. These gifts, plus the gold, symbolized pure and costly offerings worthy of a king.

The Gifts of the Magi. The word ‘frankincense’ comes from the Old French franc encens, or ‘pure incense.’ This is a fragrant balsamic resin coming from the Terebinth tree, native to Southern Arabia and India, and was used ceremonially by the Hebrews. Myrrh is the dried resin of the low-growing, thorny Cistus tree, or Rock Rose, also native to Southern Arabia and Ethiopia, and, at one time, to Palestine. This was used as a perfume base and is one ingredient of the anointing oil prescribed in Exodus 30:23. It was highly valued as a cosmetic, a deodorant, and a medicine. The Egyptians used both frankincense and myrrh in embalming. These gifts, plus the gold, symbolized pure and costly offerings worthy of a king.

The Christmas Tree. Worship of trees traces back to the Akkadians, Egyptians, Romans, Babylonians, and Druids. The Akkadians worshipped entire forest groves, later modifying them as the Asherah poles found in the Old Testament (e.g., Exodus 34:13). Trees and poles continued to be syncretized and worshipped by varying early civilizations largely in tribute to the panoply of fertility goddesses such as Ishtar, Ashteroth, Astarte, and Eastera (from which we get our name for the spring celebration of Easter). It is thought that tree decoration may have been an outgrowth of the practice of hanging foodstuffs in trees to keep them away from animals.

The Christmas Tree. Worship of trees traces back to the Akkadians, Egyptians, Romans, Babylonians, and Druids. The Akkadians worshipped entire forest groves, later modifying them as the Asherah poles found in the Old Testament (e.g., Exodus 34:13). Trees and poles continued to be syncretized and worshipped by varying early civilizations largely in tribute to the panoply of fertility goddesses such as Ishtar, Ashteroth, Astarte, and Eastera (from which we get our name for the spring celebration of Easter). It is thought that tree decoration may have been an outgrowth of the practice of hanging foodstuffs in trees to keep them away from animals.

The Egyptians believed that Isis, the queen of heaven, gave birth to a messianic son, Baal-Tamar at the time of the winter solstice, and symbolized the event with the palm tree. They also made further gestures for the pacification of Osiris with the sacrifice of a goose, a tradition which continues today in western Europe and the eastern United States.

The Romans revered the fir tree in their worship of their lord of the covenant, Baal-Berith, a belief having its roots in the Chaldean story of the infant Eol, who issued from a tree. This story also bears striking similarity to that of the Greek sun-god Adonis, whose mother mystically became a tree after giving birth to her son. Interestingly, the boars head, an English Christmas tradition, stems from the ancient Saxon sacrifice to the sun in propitiation for the loss of Adonis. Druids believed trees to be spiritual powers which could move independently and could thus influence wars and tribal events.

The first written record of a Christmas tree comes from the story of the missionary monk Winfried (or Wilfred) who was commissioned to convert the Druids in England, and later sainted for his work. According to legend, he, being surrounded with a group of his converts, struck down a huge oak tree which was the focus of the Druid’s worship. The Druid’s watched in amazement as the oak tree fell to the earth, split into four pieces, and from its center grew a small fir tree. Winfried set his axe aside and spoke to his neophytes. “This little tree shall now be your holy tree tonight, for it is the wood of peace. It shall be the sign of eternal life, symbolized by its evergreen leaves. And see how it points to heaven. Let these fir trees be called trees of the Christ-child, and of his gospel message. Gather about it not in the wilderness, but in your homes, which are also built of fir. There it will be surrounded with loving gifts and rites of kindness, by song and rejoicing.”

The westernized celebration of the Christmas tree originated in Germany several hundred years ago, having been traced back to a written record in the year 1521 in the province of Alsace along the upper Rhine River. A subsequent record comes from Strasburg in 1605, which states, “At Christmas, fir trees are set up in the rooms and hung with roses cut from paper of many colors, apples, wafers, spangle-gold, sugar, etc.” Also traditional in decorating the trees were ribbons, nuts, fruits gilded or covered with bright colored paper, toys, dolls, and glittering strings of beads. Candles later appeared in the early 1700’s when the Christmas tree custom spread throughout Germany and Austria. Beautiful but dangerous, people customarily lit the candles and watched the display only for a short time before extinguishing them. Electric lights first appeared on Christmas trees in 1882, having been invented by Thomas A. Edison as an alternative to candles.

In America, one of the first recorded uses of the Christmas tree appears to have been in 1804 at Fort Dearborn in Illinois, having been set up by American soldiers serving in the locale of present-day Chicago in the aftermath of the American Revolution. Typical early American decorations were fruit, ribbons, colored paper, cranberries, polished nuts, tufts of cotton, and strings of popcorn, the latter of which may have been used to represent snow. Apples were particularly desirable for use on Christmas trees because of their variable colors and ease of attachment.

Carols. Christmas songs originated in 12th century France when Franciscan monks took the local amorous song-dances which hailed the coming of Spring and adapted them to the celebration of the birth of Christ. The oldest extant Christmas hymn, While Shepherds Watched, was written by Nahum Tate and was set to music by George Frederich Handel in 1700. Most of the enduring carols were written in the 18th and 19th century. Hark! The Herald Angels Sing was originally titled Hymn for Christmas Day when Charles Wesley wrote it in 1739. The first line was originally “Hark, how all the welkin rings,” welkin being an Old English word referring to the heavens. Fourteen years later, George Whitefield changed the line to “Hark, the herald angels sing,” but more than a century passed before William Cummings noticed how well the words blended with Felix Mendelssohn’s famous tune, which is used today.

Carols. Christmas songs originated in 12th century France when Franciscan monks took the local amorous song-dances which hailed the coming of Spring and adapted them to the celebration of the birth of Christ. The oldest extant Christmas hymn, While Shepherds Watched, was written by Nahum Tate and was set to music by George Frederich Handel in 1700. Most of the enduring carols were written in the 18th and 19th century. Hark! The Herald Angels Sing was originally titled Hymn for Christmas Day when Charles Wesley wrote it in 1739. The first line was originally “Hark, how all the welkin rings,” welkin being an Old English word referring to the heavens. Fourteen years later, George Whitefield changed the line to “Hark, the herald angels sing,” but more than a century passed before William Cummings noticed how well the words blended with Felix Mendelssohn’s famous tune, which is used today.

Silent Night was written on Christmas Eve, 1818. When the organ broke down at St. Nicholas Church in the village of Oberndorf in Bavaria, the Vicar, Rev. Joseph Mohr needed to provide a musical substitute. Mohr wrote out the words to the Christmas song he entitled Song from Heaven, later to be renamed Silent Night, Holy Night. He asked his friend Franz Gruber, the village schoolmaster and organist, to set them to music. The two sang the song as a duet that night, with Gruber accompanying on the guitar. When the organ repairman, Karl Mauracher, heard the song, he asked for a copy and shared it around the countryside. When the Rainer and Strasser families from the Zillertal valley in Tirol, embarked on a singing tour and performed the song in New York and St. Petersburg. Silent Night. The carol was sung at the Leipzig fair in 1831, where it created such a sensation that it quickly made its way around the world.

Advent. A customary time of contemplation and preparation, Advent has parallels with the Lenten season which precedes Easter. Advent is celebrated in churches on the four Sundays prior to Christmas Day. Typically, an Advent wreath is used, comprised of holly and ivy, embellished with four red candles surrounding a central white candle. On each Sunday of Advent, a candle is lit during the service until all four red candles and the white candle are burning on Christmas day.

Advent. A customary time of contemplation and preparation, Advent has parallels with the Lenten season which precedes Easter. Advent is celebrated in churches on the four Sundays prior to Christmas Day. Typically, an Advent wreath is used, comprised of holly and ivy, embellished with four red candles surrounding a central white candle. On each Sunday of Advent, a candle is lit during the service until all four red candles and the white candle are burning on Christmas day.

Christmas Cards. Sir Henry Cole, founder of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, began this tradition in 1843 when he had little time to write his traditional Christmas letters to family and friends. He commissioned artist John Calcott Horsely to create a decorated card on which was printed Cole’s apology for not sending a personal note. By the next Christmas, the king and queen of England helped to popularize Christmas cards by enclosing them with their gifts. Following their example, the British printing company of Charles Goodall and Sons soon issued the first Christmas cards for sale to the public.

Christmas Cards. Sir Henry Cole, founder of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, began this tradition in 1843 when he had little time to write his traditional Christmas letters to family and friends. He commissioned artist John Calcott Horsely to create a decorated card on which was printed Cole’s apology for not sending a personal note. By the next Christmas, the king and queen of England helped to popularize Christmas cards by enclosing them with their gifts. Following their example, the British printing company of Charles Goodall and Sons soon issued the first Christmas cards for sale to the public.

Wassailing. Thought to derive from either the Middle English waes hael and/or the Anglo Saxon Waes pu hael, meaning ‘be thou hale’ or ‘be healthy.’ The ancient custom of orchard-visiting wassailing occurred in cider-producing regions of England and involved the reciting of incantations and singing to the trees to bring about a good harvest for the following year. This took place on Twelfth Night and began with the eating of hot cakes and the drinking of a brew of cider, brandy, ale and spices. Next, the celebrants would visit an apple tree, place a cake on the tree and splash it with cider. They would then shoot at the tree and bang pots and pans loudly banged as everyone sings a wassail song.

Wassailing. Thought to derive from either the Middle English waes hael and/or the Anglo Saxon Waes pu hael, meaning ‘be thou hale’ or ‘be healthy.’ The ancient custom of orchard-visiting wassailing occurred in cider-producing regions of England and involved the reciting of incantations and singing to the trees to bring about a good harvest for the following year. This took place on Twelfth Night and began with the eating of hot cakes and the drinking of a brew of cider, brandy, ale and spices. Next, the celebrants would visit an apple tree, place a cake on the tree and splash it with cider. They would then shoot at the tree and bang pots and pans loudly banged as everyone sings a wassail song.

In the house-visiting form of wassailing, people would go door to door, singing and offering a drink from the wassail bowl in exchange for gifts. Typically a carol such as Here We Come A-wassailing was sung to inform the lord of the house, “Love and joy come to you/ and to you your wassail too/ And God bless you and send you a Happy New Year.” The carol, ‘We Wish You a Merry Christmas,’ is thought to have originated as a wassail song. This practice was later displaced by caroling.

Mistletoe. Centuries ago, mistletoe was used by the Druids as part of their sacrifices during their winter celebrations, as the green leaves and pearl-like berries were believed to have magical healing qualities and power against evil. The Scandinavians considered the plant to be a symbol of peace, wherein enemies who met under a tree in which mistletoe was growing were bound to declare a truce for the day, sealing their treaty with a kiss. In a more spiritualized sense, mistletoe was later regarded as a “celestial branch” sent from heaven to grow upon an earthly tree, thereby symbolizing, with a kiss, the union of heaven and earth, the overcoming of sin, and divine reconciliation. The scripture which was related to this “heavenly sprig” comes from Psalm 85:10-11, Love and faithfulness meet together; righteousness and peace kiss each other. Faithfulness springs forth from the earth, and righteousness looks down from heaven.

Mistletoe. Centuries ago, mistletoe was used by the Druids as part of their sacrifices during their winter celebrations, as the green leaves and pearl-like berries were believed to have magical healing qualities and power against evil. The Scandinavians considered the plant to be a symbol of peace, wherein enemies who met under a tree in which mistletoe was growing were bound to declare a truce for the day, sealing their treaty with a kiss. In a more spiritualized sense, mistletoe was later regarded as a “celestial branch” sent from heaven to grow upon an earthly tree, thereby symbolizing, with a kiss, the union of heaven and earth, the overcoming of sin, and divine reconciliation. The scripture which was related to this “heavenly sprig” comes from Psalm 85:10-11, Love and faithfulness meet together; righteousness and peace kiss each other. Faithfulness springs forth from the earth, and righteousness looks down from heaven.

Holly and Ivy. In the circular wreath shape, holly, with its spiked leaves and blood-red berries, was symbolic of the crown of thorns. As evergreens, both holly and ivy served as reminders of eternal life and the coming of Spring.

Holly and Ivy. In the circular wreath shape, holly, with its spiked leaves and blood-red berries, was symbolic of the crown of thorns. As evergreens, both holly and ivy served as reminders of eternal life and the coming of Spring.

Centuries ago, Romans used holly as decoration for their Saturnalia celebrations. Norse mythology associated holly with Thor, the god of thunder and grew holly near their homes, believing it to prevent lightning strikes.

Ivy was symbolic of marriage and friendship and in some cultures, thought to have magical powers sufficient to keep houses safe from demons. In ancient Rome, ivy was associated with Bacchus, the god of wine and revelry.

Poinsettia. This traditional Christmas plant, called Flor de la Noche Buena, or Flower of the Holy Night (Christmas Eve flower) in Mexico. It was discovered there by Dr. Joel Poinsett, the first U.S. Minister to Mexico, who introduced the plant to the United States in 1825. In the 16th century, the poinsettia was adapted for use at Christmas in Mexico because of its red and green color and its star-shaped leaf pattern, symbolizing the Star of Bethlehem. Legend has it that Pepita, too poor to offer a gift for the Christ-child, was inspired by an angel to gather weeds from the roadside and place them in front of the altar, from which grew the poinsettia. In Spain, the flower is known as Flor de Pascua (Easter flower) and in Chile and Peru, it is called the Crown of the Andes. Hungarians refer to it as the Santa Claus flower. In the U.S., December 12 is recognized as National Poinsettia Day.

Poinsettia. This traditional Christmas plant, called Flor de la Noche Buena, or Flower of the Holy Night (Christmas Eve flower) in Mexico. It was discovered there by Dr. Joel Poinsett, the first U.S. Minister to Mexico, who introduced the plant to the United States in 1825. In the 16th century, the poinsettia was adapted for use at Christmas in Mexico because of its red and green color and its star-shaped leaf pattern, symbolizing the Star of Bethlehem. Legend has it that Pepita, too poor to offer a gift for the Christ-child, was inspired by an angel to gather weeds from the roadside and place them in front of the altar, from which grew the poinsettia. In Spain, the flower is known as Flor de Pascua (Easter flower) and in Chile and Peru, it is called the Crown of the Andes. Hungarians refer to it as the Santa Claus flower. In the U.S., December 12 is recognized as National Poinsettia Day.

The Yule Log. This tradition originates from Scandinavian festivals, which was spread throughout Europe during the Viking conquests. Custom states that a log be chosen in the forest, decorated with ribbons, and brought home. On the homeward journey, anyone meeting the procession was to salute the log by raising their hat. Once home, the Yule Log was lit on Christmas Day and burnt throughout the twelve days of Christmas. The remains of the log were then retained as kindling, to be used to ignite the Yule Log for the next Christmas. In Cornwall, the Yule Log was known as the Mock, and children were encouraged to stay awake until midnight when they would drink the Mock for good luck. Called the ashen faggot in Devon, the log is comprised of bundles of ash sticks bound together, carried home, placed in the fireplace and ignited with a piece of the previous years’ ashen faggot.

The Yule Log. This tradition originates from Scandinavian festivals, which was spread throughout Europe during the Viking conquests. Custom states that a log be chosen in the forest, decorated with ribbons, and brought home. On the homeward journey, anyone meeting the procession was to salute the log by raising their hat. Once home, the Yule Log was lit on Christmas Day and burnt throughout the twelve days of Christmas. The remains of the log were then retained as kindling, to be used to ignite the Yule Log for the next Christmas. In Cornwall, the Yule Log was known as the Mock, and children were encouraged to stay awake until midnight when they would drink the Mock for good luck. Called the ashen faggot in Devon, the log is comprised of bundles of ash sticks bound together, carried home, placed in the fireplace and ignited with a piece of the previous years’ ashen faggot.

The Candy Cane. It was December 1670, in Cologne, Germany when the choirmaster at Cologne Cathedral sought to alleviate the noise children caused during their Living Creche tradition of Christmas Eve. He asked a local candymaker to make ‘sugar sticks’ with a crook on one end to remind the children of the shepherds who came to visit the Christ child. The sugar sticks should be white, he said, to remind the children of Jesus’ sinless life. Another tradition designated the red stripe as a reminder of Jesus’ shed blood.

The Candy Cane. It was December 1670, in Cologne, Germany when the choirmaster at Cologne Cathedral sought to alleviate the noise children caused during their Living Creche tradition of Christmas Eve. He asked a local candymaker to make ‘sugar sticks’ with a crook on one end to remind the children of the shepherds who came to visit the Christ child. The sugar sticks should be white, he said, to remind the children of Jesus’ sinless life. Another tradition designated the red stripe as a reminder of Jesus’ shed blood.

Come 1919 in Albany, Georgia, Robert McCormack began making candy canes for local children; his company, the Mills-McCormack Candy Company, became one of the world’s leading makers of candy canes.

Santa Claus. The real Saint Nicholas, the fourth century bishop of Myra in Turkey, was a precocious child, was born in 271 AD to a wealthy Christian family in the town of Patara, and as a young man, was passionate in his defense of the Christian faith. When his parents died in an epidemic, he gave away all his wealth and entered the priesthood. Nicholas later assumed the office of bishop where he became known as a ‘righter of wrongs’ who protected children, the innocent, and those in need.

Santa Claus. The real Saint Nicholas, the fourth century bishop of Myra in Turkey, was a precocious child, was born in 271 AD to a wealthy Christian family in the town of Patara, and as a young man, was passionate in his defense of the Christian faith. When his parents died in an epidemic, he gave away all his wealth and entered the priesthood. Nicholas later assumed the office of bishop where he became known as a ‘righter of wrongs’ who protected children, the innocent, and those in need.

Legend tells that Nicholas became aware of the distress of a poor family with three daughters. Without a dowry, the daughters faced being sold into prostitution. Nicholas, in his compassion, dropped a dowry gift of gold coins through their window where it fell into a stocking. This act seems to have been the origin of the tradition of hanging stockings on the mantle. He is also attributed to have restored three students to life who had been brutally killed.

Long considered by the Roman church as the third figure in importance after Jesus and Mary, Nicholas has been the patron saint of children, noted for his generous giving of money and gifts to the needy. His legend, as it grew throughout Western Europe, became syncretized with that of the mystical Germanic Wodin, who was said to ride through the sky on his eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, wearing a long blue hooded cloak and making judgments on those who were good and evil. Wodin manifested twelve characters, one for each month. The character for December was known as Jule, hence Jultid, or Yuletide. In the twelfth century, French nuns distributed candy in the name of St. Nicholas, leaving their gifts in children’s shoes on doorsteps; Martin Luther, referring to St. Nicholas’ as Kris Kringle, recognized his good deeds as similar in kind to those of Jesus Christ himself.

The name Santa Claus comes from the Dutch Sinter Klaas, or Saint Claus, Claus being the Dutch translation for Nicholas. He was popularized by Washington Irving in his Knickerbocker History about the Dutch influence in New York. Santa Claus’ red-suited attire also stems from the traditional European dress of a red coat, white robe, and pointed hat.

In Holland, Sinter Klaas rides a white horse and is assisted by his Moorish elf, Black Peter, who carries a birch rod and a sack of goodies. In today’s tradition, the Dutch leave a shoe outside their doors on the eve of December 5 in hopes that a gift will be left in it.

In England, he is known as Father Christmas and closely resembles his American cousin, except his coat and beard are considerably longer. In France, he is known as Pere Noel or Pere Fouttard, depending on the locale and tradition. In Luxembourg, he is Hoesecker and in Germany, gifts are delivered by Berchta, Knect Ruprecht, and Christindl, the Christ Child, In Italy, gifts are delivered by the mythical woman, La Bufana. In Sweden, gifts are brought by an elf named Jultomten, who resembles a miniature Santa Claus as he drives his sleigh pulled by two goats. In Brazil, there is Papa Noel, while in Costa Rica, Columbia, and parts of Mexico, El Nino Jesus, the infant Jesus, continues in this tradition. In the Gullah tradition of North Carolina, he is represented as a black Sandy Claw.

Many forms of the St. Nicholas tradition in Europe have assistants whose job it is to deal with naughty children by leaving switches cut from trees for their parents to discipline them with and carries the truly bad children away in his bag until they can learn to be good.

New York Theological Seminary professor Dr. Clement C. Moore’s poem The Visit from St. Nicholas, first published in 1823 and later re-titled The Night Before Christmas, is the principal source of the United States traditional Santa Claus imagery as well as that of the flying reindeer and sleigh and gifts being delivered via the chimney. Moore’s poem was first illustrated by New York Times political cartoonist Thomas Nast. Katherine Lee Bates, who wrote America the Beautiful, initiated the idea of Mrs. Claus.

As Christians, which of these many traditions, if any, should we observe? Throughout the Christmas season, we will often hear the phrase, “This is what Christmas is all about,” referring to family, love, giving, celebrating, or whatever else might seem appropriate to the moment. Moreover, a mythic Santa Claus seems to receive pre-eminence as the author of ‘Peace on earth, good will to all,’ literally usurping the role from Jesus Christ. Less and less frequently do references to Christmas have to do with the celebration and recognition of the coming of Jesus Christ to this world. Every year, Christmas becomes more secularized and reduced to represent a time in which warm fuzzy feelings are the ultimate goal for children and adults alike. Little mention or credence is given to Christmas as the celebration of the birth of Christ.

As Christians, which of these many traditions, if any, should we observe? Throughout the Christmas season, we will often hear the phrase, “This is what Christmas is all about,” referring to family, love, giving, celebrating, or whatever else might seem appropriate to the moment. Moreover, a mythic Santa Claus seems to receive pre-eminence as the author of ‘Peace on earth, good will to all,’ literally usurping the role from Jesus Christ. Less and less frequently do references to Christmas have to do with the celebration and recognition of the coming of Jesus Christ to this world. Every year, Christmas becomes more secularized and reduced to represent a time in which warm fuzzy feelings are the ultimate goal for children and adults alike. Little mention or credence is given to Christmas as the celebration of the birth of Christ.

Yet there is a glimmer of hope, for selfless giving seems to be more evident every year and serves to convey the hopeful message of the gospel.

But the traditions themselves have a positive aspect, for they provide us with continuity and identity as families and as a people, furnishing us with a rich tapestry of joyous celebration. As long as they are given their proper perspective, there are no biblical restrictions to their observance. What is done with these Christmas traditions, however, is significant, for as important as they are to our holiday celebrations, they are never more important than the object of our celebration, who is Jesus Christ, our Savior, our deliverer from sin, and our reconciler to God. With this in mind and heart, we can rejoice, singing, For unto us, a son is born, a son is given!